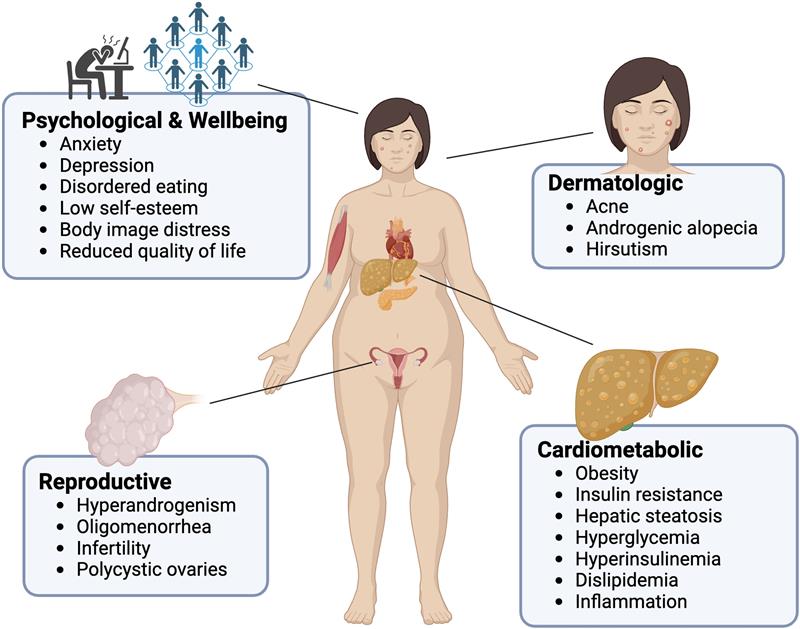

Addressing insulin resistance through evidence-based strategies including regular physical activity, balanced macronutrient intake, and adequate sleep. Structured exercise interventions have demonstrated measurable improvements in insulin sensitivity and cardiometabolic markers in individuals with PCOS [8]. These behavioral factors influence insulin sensitivity and hormonal regulation.

Sleep itself modulates insulin signaling and hypothalamic function. Chronic sleep deprivation alters cortisol patterns and metabolic stability. For physicians in training, protecting sleep is not indulgence. It is endocrine protection.

Stress management is similarly physiologic, not cosmetic. Chronic activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis interacts with metabolic and reproductive signaling. Structured exercise, restorative practices, and mental health support are not peripheral wellness trends. They influence endocrine balance directly.

Finally, self-advocacy matters. Seeking medical evaluation when symptoms persist. Requesting appropriate referrals. Not minimizing symptoms because we feel we “should handle it.” Preventive medicine does not exclude the provider. Ultimately, what begins as a calendar irregularity can reflect years of underlying endocrine signaling. If we believe early detection reduces long-term cardiometabolic and oncologic risk, that belief must apply inward. Ignoring persistent irregular cycles risks reinforcing the historical minimization of women’s symptoms and delayed endocrine diagnosis.

PCOS illustrates something larger than a diagnostic algorithm. It shows how reproductive health, metabolic regulation, oncologic risk, and psychological well-being are interconnected. Irregular periods are not trivial. They are physiologic signals. As future physicians, we are trained to interpret signals carefully. That responsibility does not end with patient encounters.

Menstrual health deserves the same seriousness we give every other vital sign.

References

1. International Evidence-Based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome 2018. Monash University; 2018. Updated 2023.

2. Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 2013;98(12):4565-4592. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2350

3. AMBOSS. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. AMBOSS Medical Knowledge Library. Updated

2024. Available at: https://www.amboss.com

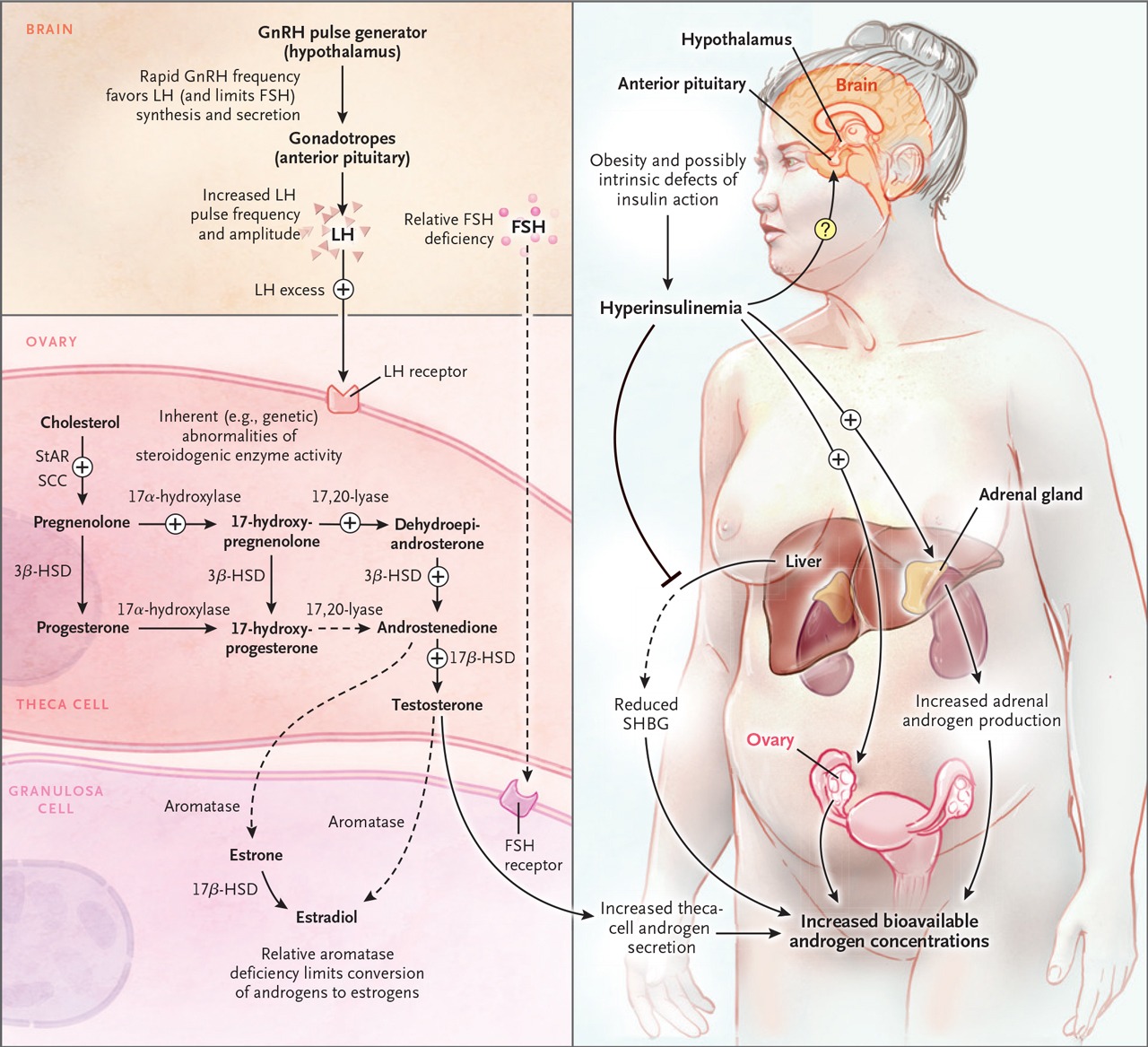

4. Rosenfield RL, Ehrmann DA. The pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J

Med. 2016;374(1):54–64. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1415564

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 194:

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):e157–e171.

doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002656

6. Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(6):476–491.

doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30045-5

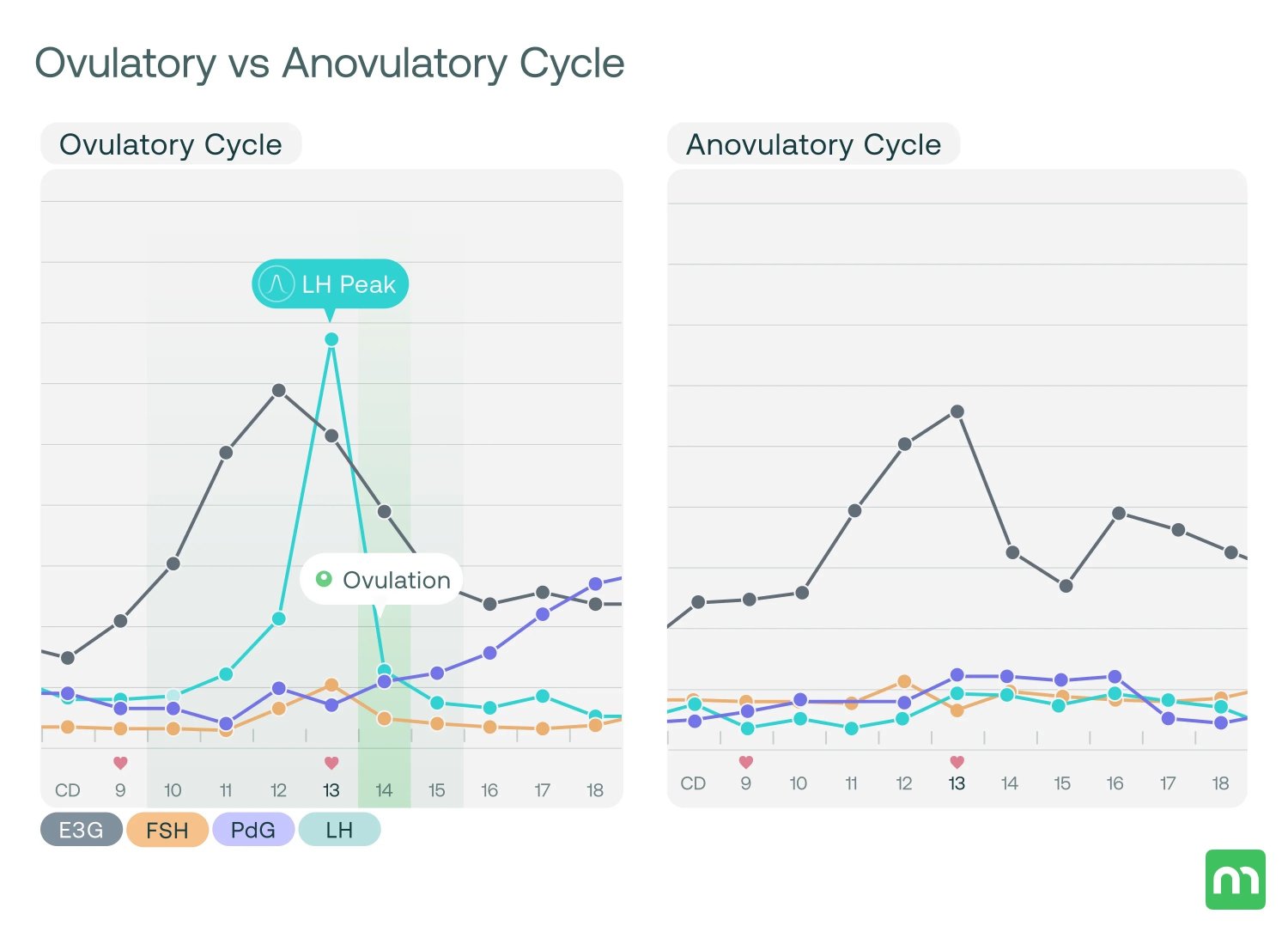

7. MiraCare. Anovulatory Cycle Explained: What Is It and How to Prevent It. MiraCare

Blog. Available at: https://shop.miracare.com/en-int/blogs/resources/anovulatory-cycle-explained-what-is-it�and-how-to-prevent-it

8. Sabag A. Exercise in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome. J Sci Med Sport.

2024. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2024.05.01